Funny how the new things are the old things.

Rudyard Kipling.

A story in a recent issue of Hi-Fi News and Record Review led me to reflect on long-term changes in the world of hi-fi – not only changes in equipment, but also changes in how we think about hi-fi.

I was browsing through that glossy magazine when I saw a report on the 2016 Munich High End show. The story was near the front of the magazine but, in a gesture of unconscious obeisance to the god of retro, I tend to start at the back, going straight to the things that interest me most: music stories, vintage-equipment reviews, and those tantalising advertisements from British second-hand dealers where, as though looking through a medieval bestiary, one finds exotic, quasi-mythological hi-fi creatures such as Transcriptors turntables.

But speaking of retro, the ‘new releases’ featured in the article about the Munich show included amplifiers by Dynaco and Hafler, and turntables from Perpetuum-Ebner. Until recently all these brands were dead (though apparently not, to quote a recent head of state, buried and cremated). What really caught my eye at Munich, though, was a high-end turntable from Elac, who have got back into vinyl by resurrecting their once popular Miracord range with the striking, limited-edition Miracord 90.

Naturally enough it occurred to me that a magazine story involving similar products from these manufacturers might have been written about a Munich hi-fi show of 50 years ago or more. But how is this possible when there have been so many changes in hi-fi over the years, and when hi-fi itself, as a branch of science and technology, is predicated on ideas of innovation and progress? It seems that within hi-fi at the moment there are two contradictory historical visions: on the one hand, belief in technological progress surely remains most people’s default position; yet, on the other hand, it is difficult to make sense of the ‘new’ products at Munich without using metaphors of cycles, spirals, and even, to borrow an idea from Nietzsche, eternal return.

And as well as these two contradictory ideas about the overall history of hi-fi, this history can itself be broken down into several distinct stages, each of which was defined by a specific approach to the hi-fi system – in other words, by an idea. For example, when hi-fi as we know it began in the 1950s, it was thought that the speakers were the most important part of the system. This made a lot of sense because, after all, everything you hear comes out of the speakers, and notable developments in speakers such as the Acoustic Research range and Quad ESL 57 electrostatics reflected this thinking. By the 1970s, however, it was felt that the amplifier, as the ‘heart’ of the system, was the most important component. This made a lot of sense because, after all, everything you hear comes through the amplifier, and at the time there was a significant R&D emphasis on amplifiers, as seen in innovations such as the widespread use of transistors, and in the emergence of American muscle amps. But in the 1980s it was felt that the source was the most important component. This made a lot of sense because, after all, everything you hear comes from whatever source you are using. The source in question was, of course, ideally a Linn LP 12, which was the standard-bearer of the two dominant concepts of the day: hierarchy, and the quasi-mystical ‘musicality’.

Hierarchy was, however, eventually replaced by synergy or, to be less mystical, compatibility. It was now felt that how various components suited each other was more important than any overarching order or pattern. This also made a lot of sense. And it still does because it is more or less how things stand today.

The idea of overall progress informed all of these epoch-defining approaches. We are nevertheless entitled to ask – and the recent emphasis on all things retro casts this question into much sharper relief – whether these changes in approach actually amount to progress, or whether we have just been moving from one conceptual paradigm to another. If the latter is the case, then progress is a myth and we have been chasing will o’ the wisps all this time.

Is it even possible to answer this question? Strictly speaking, it is not, for to be able to do so would involve possessing a perspective that somehow transcends one’s immediate paradigm. But it is surely permissible to draw upon our own experiences in thinking about such questions. In my case, a comparison between a system I had around 1980 and the one I have now comes to mind. Simply put, is the one I have now better? If I were to answer ‘no’, it would be because of the magnificently wide and precisely positioned sound stage that my old Amcron electrostatic-conventional hybrid speakers presented when I played records on my AR turntable with its JH arm and Nakamichi moving-coil cartridge. I have been attempting to recapture that soundstage ever since, along the way making a virtue out of a necessity by trying to convince myself that musical coherence is more important than the clear separation of instruments, tracks, and channels.

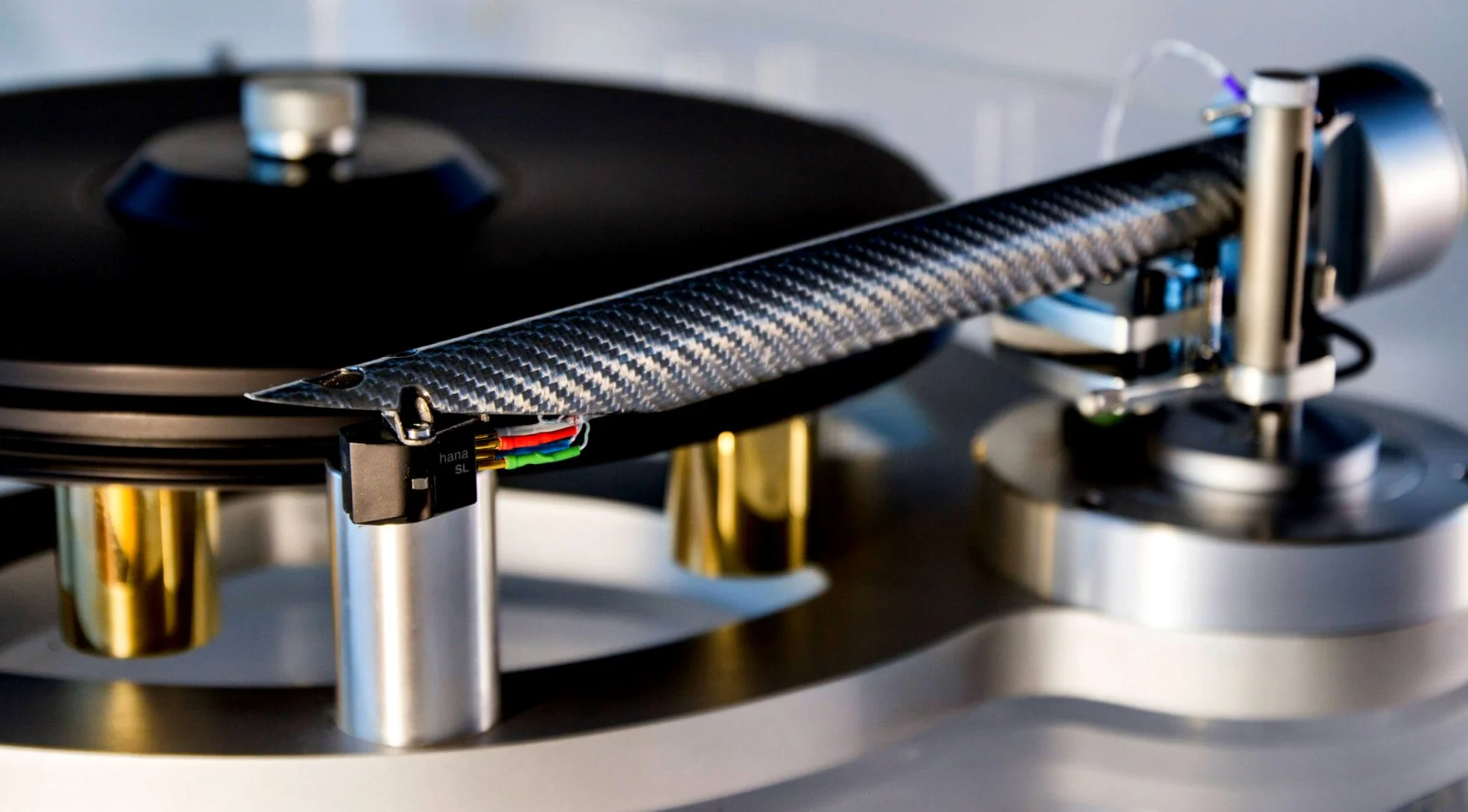

There is, of course, also a ‘yes’ answer. I’m sure, for example, that my current Merlin-Naquadria amplifiers are much better than my 1980 Amcron-Dynaco combination and, for that matter, everything else I’ve ever had including the celebrated Naim 250 power amp. I also feel that a decent medium-priced modern tonearm represents a significant improvement on even state-of-the-art vintage arms. This opinion was confirmed recently when I replaced the early-model SME 3009 on my vintage Orpheus turntable with a 9” version of The Wand carbon-fibre tonearm from Design Build Listen in New Zealand. One reason for the huge improvement I perceived is the tonearm cabling involved, and I think that cabling in general is an area where one may well speak of progress; I shudder to think that in 1980 I was feeding my Amcron electrostatics with the sort of speaker wire that one buys at Bunnings these days. Cabling aside, though, current unipivot tonearms like The Wand still seem better than their antecedents such as the once highly regarded JH Formula 4 and even the legendary Naim Aro.

The Wand. Sci-fi Hi-fi.

But, as I’ve said before, the thing to do is to put something like The Wand on a good vintage turntable. In fact, my two current favourite turntables, the Orpheus and a souped-up Thorens TD 160, both have Wands. The Orpheus is from the late 1950s and the Thorens the 1970s. The Orpheus has an Ortofon 2M Black cartridge, which is a – perhaps the – current cutting-edge moving-magnet design, while the Thorens has a Decca London cartridge, which, although new, is essentially the same design as its Decca predecessors from the 1950s. Do these various combinations of old and new amount to progress? Again, there is both a ‘yes’ and a ‘no’ answer. But perhaps coming to grips with the issue of hi-fi progress means that we need to re-think the very idea of progress, not least because many a hi-fi great leap forward seems also to have involved something being lost. For now, though, that Elac Miracord 90 turntable, the apotheosis of the whole new-old thing, is mighty tempting. It’s calling me with its Siren song. Wax, anybody?

Dr Walter Kudrycz