I was thinking about retro hi-fi gear recently when a certain medieval monk came to mind. Perhaps it wasn’t the most obvious of segues, but I happened to recall that Gilbert of Nogent, who was abbot of a monastery in Northern France in the early twelfth century, had railed against a desire for new things. Gilbert left a large body of works including an autobiography and a history of the First Crusade. Gilbert didn’t like a lot of what was going on around him, especially outpourings of popular enthusiasm like the ‘Peoples Crusade’ and a communal uprising in nearby Laon. He attributed these disturbances to a desire for novelty among the ill-informed; he felt that in their ignorance the common people had lost touch with what was of real value, and had been led into excess, false hope, and sin.

If it sounds half as good as it looks...

Are those of us into retro hi-fi gear the modern equivalents of Gilbert? Of course we are. We think that we have avoided thraldom to a demonic late capitalism with its endless cycles of constructed consumerism. We find value beyond fads and fashion – beyond novelty.

But I have to confess that I’m an apostate: I bought the new ‘anniversary-edition’ Miracord 90 turntable by Elac. It was like the Temptation of Saint Anthony. The svelte Elac, with its beguiling minimalism, is so damned beautiful that merely looking at pictures of it seems to blacken the soul. Its nostalgic links with Elac Miracord turntables of the past also enabled me to tell myself that it wasn’t entirely new anyway. Well, they say that nostalgia isn’t what it used to be. But neither, as I found out, is novelty because acquiring the new Elac turned out to be both a pleasing and a disappointing experience – as is more-or-less inevitable, I guess, when, Oscar Wilde style, one resists a temptation by yielding to it.

The Elac/Wand: Art Deco meets Blake's Seven in an unlikely synergy.

I wasn’t tempted just by the Elac’s looks, either; it’s also appealing because it’s clever. Suspended sub-chassis are no longer fashionable, which means that motor vibrations are potentially more of an issue in belt-drive turntables than they once were. Elac have, however, encased the motor in a high-tech gauzy material, thereby in effect decoupling it from the plinth (and therefore from the platter). The motor itself is also a DC unit, so it should be relatively smooth in any case.

The electronically speed-controlled platter is heavy, too, weighing in at 6.5 kilos. I have, by the way, increasingly come to regard a heavy platter as a – or perhaps the – sine qua non of good turntable performance.

So, buoyed by these impressive design features, and with a potent cocktail of anticipation, trepidation, and guilty apostasy coursing through my veins, I had a listen. How did it sound? Pretty good: it presented a nice sound-stage and the musical instruments were clearly defined. But naturally I had to compare it with something else, so I switched to my old Orpheus turntable. In retrospect, I realise that I was trying to be kind to the beautiful new Elac as the Orpheus doesn’t sound quite as dynamic my other turntables – probably because it’s a hybrid idler-belt unit, rather than a pure idler drive. The Orpheus nevertheless blew the Elac away in terms of pace, excitement, and even detail.

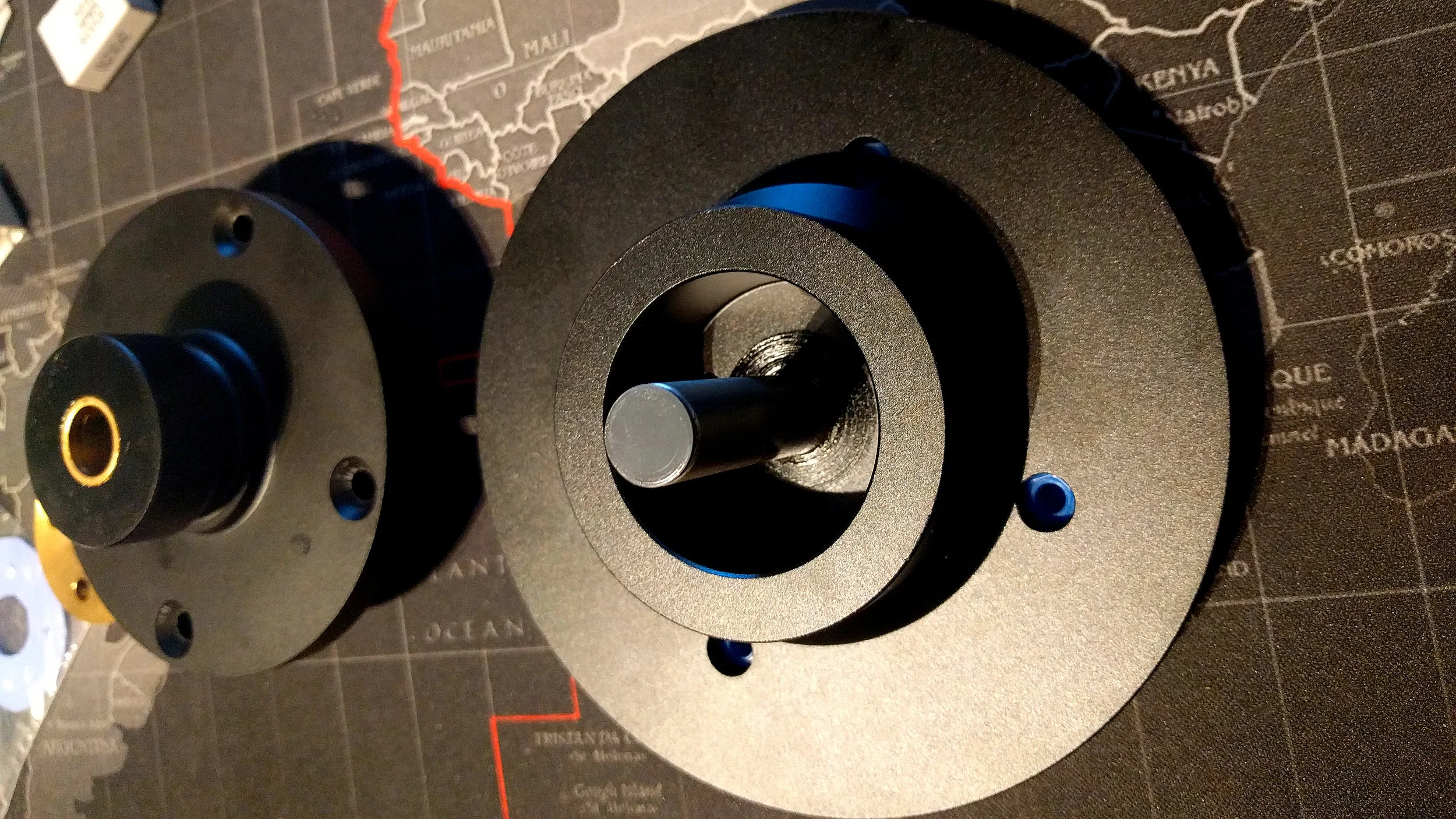

But the old Orpheus is fitted with a Wand unipivot tonearm from the superbly named Design Build Listen in New Zealand and an Ortofon 2M Black pick-up cartridge. For a comparison between the two turntables to be meaningful, I’d need the same arm-cartridge set-up on the Elac. I had reservations about the Elac arm anyway – it looked like an OEM subcontract job – so I ordered another Wand from Simon at Design Build Listen.

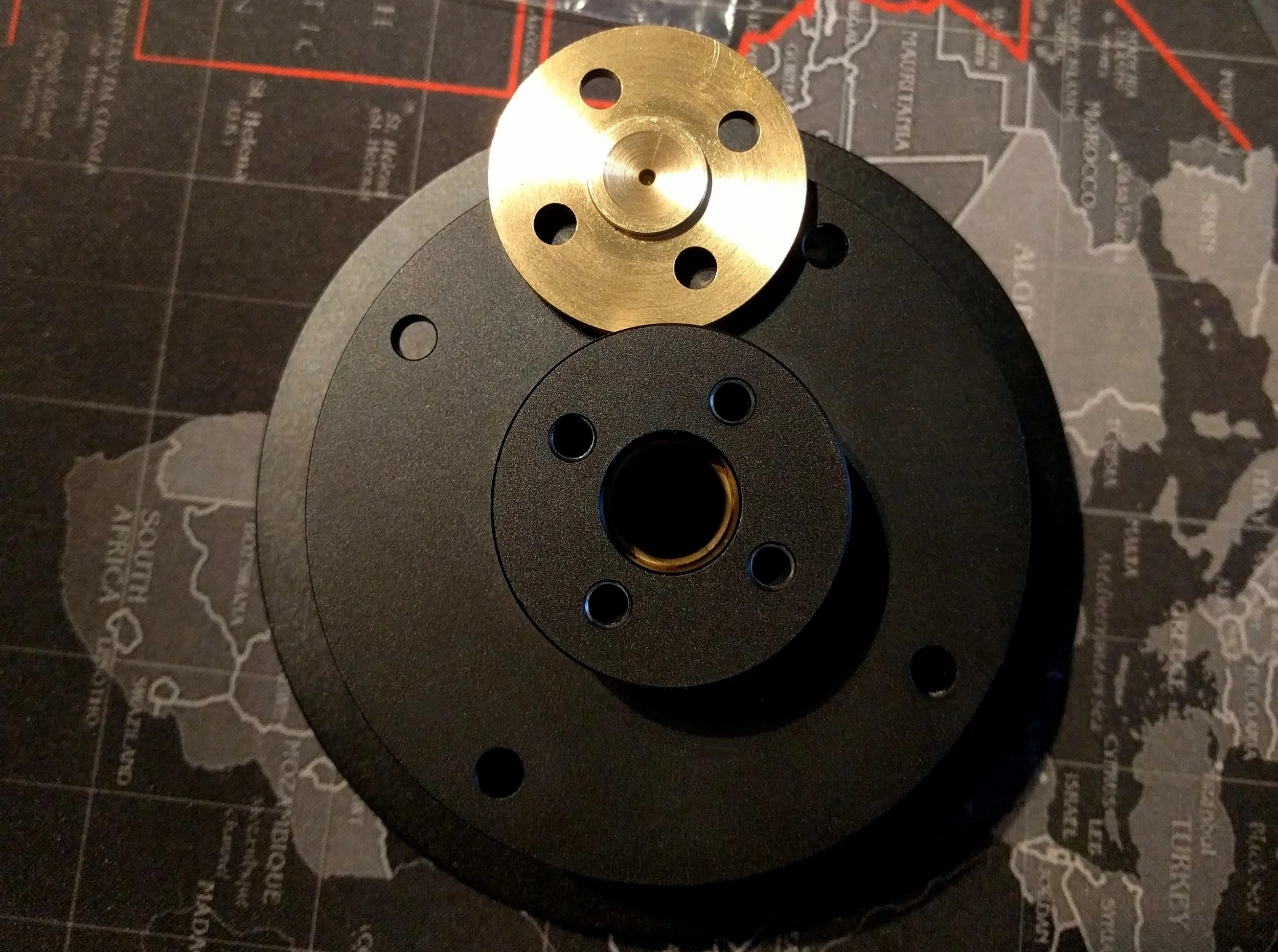

While waiting for the Wand to arrive, Bill from The Factory and I examined the Elac’s main bearing. Bill had suggested this. I was sceptical, but I humoured him. I’m glad I did because we found that there was no lubrication at all in the bearing except for a thin smear of grease. I was shocked, but worse was to come. The sapphire ball bearing had already begun to wear the end of the spindle – after about 30 minutes playing time! We then discovered that the brass thrust plate had a hole in it right under where the bearing sits. I was dumbfounded. For the hole can only have been put there so that any lubricant that happened to be in the bearing would drain out.

The Elac thrust plate and lower spindle sleeve. A ruby ball resides on the thrust plate, between it and the heavy platter's spindle base.

Fortunately I have some tiny Teflon pads I bought from Italian e-bay seller Audiosilente to upgrade the bearing on my Lenco turntable. I attached one of these to the tip of the Elac spindle to cover the wear and to reduce friction, and I glued another under the thrust plate to block the hole there. I then did something radical: I put oil in the bearing.

The upper sleeve and spindle/sub platter. Combined with the thrust plate and lower sleeve above, it now accommodates a huge oil reservoir.

Having recovered from my post-purchase tristesse, with a Wand tonearm and Ortofon cartridge installed, and comforted by knowing that the turntable wasn’t destroying itself as it played records, I felt good. My mood of elation – perhaps that cocktail again – spilled over into my first listening session with the new and now improved Elac. The sound was much better, with excellent space and good, tight bass. For once, you could appreciate the bass on The Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet, for example. This gave Sympathy for the Devil even more clout than usual (though I did wonder what Gilbert would have made of the song). But the standout characteristic of the turntable-arm-cartridge combination was its presentation of musical detail. The final song on Beggars Banquet, Salt of the Earth, has always struck me as being rather overblown and shambolic, but I was now able to discern the various components in that song’s wall of sound, and to see them all working together as music. The music itself, too, emerged out of an inky blackness; the ‘noise floor’, without a whiff of rumble or vibration, was subterranean.

But I was about to discover that novelty could be even further improved.

More Wands than Hogwarts...

A while back Bill made a control box/power supply for me when he installed a DC motor in my old Thorens TD 160 belt-drive turntable. He now suggested that we run the Elac from the same box. I remembered that the DC motor with its power supply had made a huge difference to the Thorens, particularly in terms of rhythm and dynamics, so I thought that something along the same lines would occur with the Elac. Surprisingly, though, that didn’t happen; there was a significant improvement, but it was in musical detail rather than dynamics. In other words, the already existing characteristic strength of the Elac turntable had been further strengthened.

The new and improved Elac can now hold its own against my other turntables. Yet I’ve found that comparing it with the others in any conventional A-B sense tends to undermine the very idea of qualitative comparison because these ‘comparisons’ merely highlight the different characteristics of the various turntables. This is most evident when going from the Elac to my Lenco. The Elac is subtle, detailed, and neutral (in a good way), while the Lenco is so dynamic that it feels like you’re listening to a pile-driver (in a good way). I nevertheless feel that while I’ve probably got the best out of the Lenco already, the seductive neutrality of the Elac means that it still has more to offer; it should, for instance, turn out to be an ideal platform for on-going experimentation with different cartridges.

A Decca London grazing peacefully in its natural habitat; the uni-pivot Wand.

So the Elac began as a temptation, a flirtation with novelty, and ended up in my turntable pantheon. It’s not better or worse than the other deities there; it’s just different. But that’s what it is now. In contrast, the way it was when fresh out of the box surely vindicates Gilbert of Nogent’s distrust of novelty. Not that I can claim to be in Gilbert’s good books, though, for whichever way I squirm, I can’t deny that by worshipping at the altar of novelty, I have sold my soul to the Devil. But like Faust, I’m happy. For now.

Dr Walter Kudrycz